Short review originally posted on Goodreads:

The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit by Michael Finkel

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I was so glad to find this book while browsing — I remembered this story in the news, and being fascinated. Finkel’s finely articulated and well-researched exploration of Knight’s choices, his experiences and the repercussions, helped to answer many questions I had, and raised others.

Synopsis:

Many people dream of escaping modern life. Most will never act on it–but in 1986, twenty-year-old Christopher Knight did just that when he left his home in Massachusetts, drove to Maine, and disappeared into the woods. He would not have a conversation with another person for the next twenty-seven years.

Drawing on extensive interviews with Knight himself, journalist Michael Finkel shows how Knight lived in a tent in a secluded encampment, developing ingenious ways to store provisions and stave off frostbite during the winters. A former alarm technician, he stealthily broke into nearby cottages for food, books, and supplies, taking only what he needed but sowing unease in a community plagued by his mysterious burglaries. Since returning to the world, he has faced unique challenges–and compelled us to reexamine our assumptions about what makes a good life. By turns riveting and thought-provoking, The Stranger in the Woods gives us a deeply moving portrait of a man determined to live his own way.

Further Thoughts . . .

One of the reasons I found myself connecting deeply to this story is that at one point, growing up, I was labelled a hermit by kids my own age.

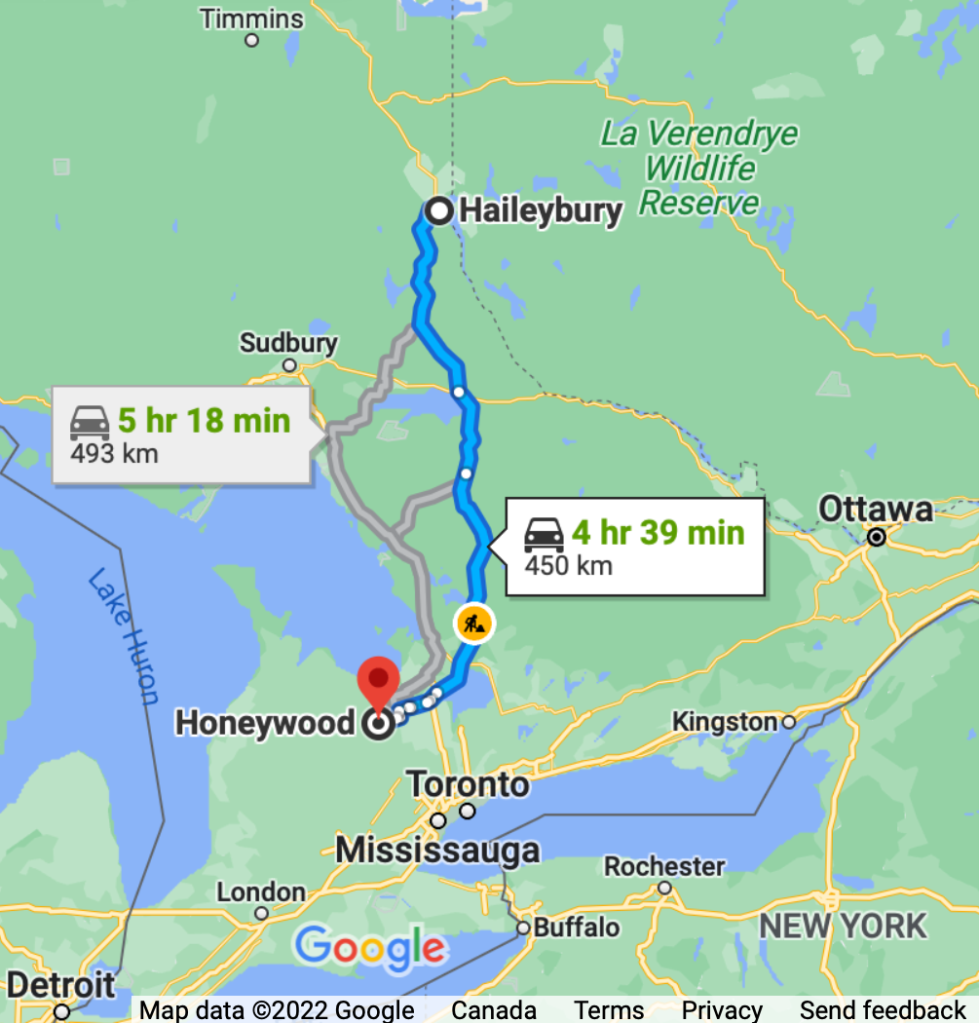

My family had moved to a hamlet called Honeywood twenty minutes outside the farming community of Shelburne, several hours away from the place where I’d started my adolescence, Haileybury.

I was okay with changing where we lived again, to keep up with my father’s promotions. Moving was an adventure, a chance to start over and have a new place to arrange things. When I was ten, I’d contemplated moving to a new place as an opportunity to reinvent myself, just a little, but that didn’t really happen.

And then I unintentionally became, at least for a few months, and in the eyes of others my age, a hermit.

My impression at the time, upon arrival, was that Honeywood was tiny. Just a handful of houses on a crossroads in Dufferin County. (It’s still an agricultural area now, and Honeywood is still classified as a hamlet.)

It was all very flat, the cluster of ten to fifteen homes surrounded by farm fields and few trees. It had one corner / general store, sitting adjacent to our house.

It was through that store and its small VHS section that I watched The Princess Bride for the first time.

I was thirteen, and we were unpacking in a large, old rental home that had, at various times, been a farm house and a bank. I loved the layout of our new house, but not the location of the bathroom — the original structure had not included indoor facilities. A single washroom had been built some time in the mid-20th century over the furthest corner of a later addition, a sunroom / breakfast nook off the kitchen that led to a sunken rec room we ended up using as storage. The shower and toilet were above that rec room. Having to journey from my bedroom on the second floor and at the front of the house, through the whole building, to pee, etc., may have added to an awkwardness that I hadn’t experienced before in a move.

In our previous town, I’d gotten used to biking around to various points of interest and services, like local parks, the library, the stores that had candy, old graveyards, trails in the woods, and we’d been fortunate that Haileybury was built on the shores of Lake Timiskaming — it had a beautiful beach with a waterslide, as well as a marina. Honeywood had two straight roads bisecting neatly ploughed and planted rows of corn, and that corner store. Was the arena already there when we moved in? If so, I didn’t go see it, because I don’t recall it at all.

After we’d unpacked the truck and gotten more settled, I did try taking my bike down the stretch of Line 2 West that ended in a stop sign in front of my house. But my bike had a problem with one pedal, so I couldn’t ride very well, pumping with just one leg. And the terrain rose after a certain distance. If I went any further, cresting a rise and descending toward a copse of woods, I knew I’d not be able to see my house at all. That was too far for my comfort level, so I turned the bike around and went home.

I believe that short-lived bike ride came in part as a result of overhearing the local kids calling me a hermit. Was it a matter of days, weeks, or a month post-possession of the property? I don’t recall the length of time. I remember taking my time to unpack my things, deciding on the position of my bed and my dresser, side table and shelves, while my older brother was content to leave much of his things in their boxes, using his free time to get out and about, engaging with those same local kids and following them on his bike to find the hang out spots and trails only they knew of.

I remember, one day, looking out my partially-open window as I fiddled with my books and knick knacks, seeing the little gathering of adolescents on bicycles either waiting for or chatting with my brother, and hearing them talk about me. About why I never came out of the house. One or two glanced up and made eye contact with me. I backed away, and was careful when I looked outside again, for a long time after that.

Contentment was in my nest, away from prying eyes and the process of having to get to know other kids all over again. I missed what routine I’d had before, but as long as I had my books, my journals, and my hobbies, I was okay. When I wasn’t in school, I tried learning magic tricks, arranged and rearranged my collections of miniature figurines and furniture, listened to the radio, and wrote letters to the friends I’d left behind. Eventually I got up the courage to cross to the corner store for penny candy or popsicles, the occasional magazine or Archie comic, and to rent movies. But I didn’t make any friends in Honeywood. Not even through a few babysitting jobs with families just a house or two down the road.

I was good with not making friends, at the time. I missed having some companionship, but sharing company can lead to conflict and unhappiness. Being by myself was simpler. Easier. Peaceful.

So when I read The Stranger in the Woods, I found much of Christopher Knight’s rationale for backing out of the world (as recorded by Michael Finkel) to be deeply relatable. I’m one of those who found the 2020 lockdown to be a relief rather than a stress, giving me a good reason or allowance to close off from personal contact with others than my immediate household.

But I’m not a true hermit, though the under-15 set of Honeywood in 1990 would disagree. I think what that experience helped to me to understand is that I’m less of a country person and more of an urban creature. I don’t know that I could exist comfortably in a rural isolation, at least, not without my library and my hobbies. My preference is to be within reasonable walking proximity to stores, parks, and services, especially now that I no longer drive. Yet I’m comfortable being on my own, going for long periods without talking to or interacting with others. Can true hermits exist within urban areas? It’s an interesting question, but I suspect, likely not.

I found that reading this book — this accounting of one individual’s experience in extended withdrawal from society, how he survived and coped and thought — gave me much to reflect on. There is a lot to unpack, especially regarding the nature of community and its requirements for membership. The price that is paid by those who feel uncomfortable being actively part of society, but have little choice other than continuing to interact. What it means when leadership rejects those individuals’ desires to be left alone, requesting and expecting and enforcing involvement, seeing community involvement on even the most basic level as a necessary component of being human. The moment when Christopher Knight was in court after completing his required rehabilitation and probation program, visibly surrendering as the judge declared that he had officially succeeded in re-entering community life, was deeply affecting for me. I’ll be reading this book again. And I sincerely hope that Mr. Knight is okay. If Michael Finkel ever sees this, thank you for sharing his story in such a sensitive and thorough way.